Subscribe to be notified if similar examples become available.

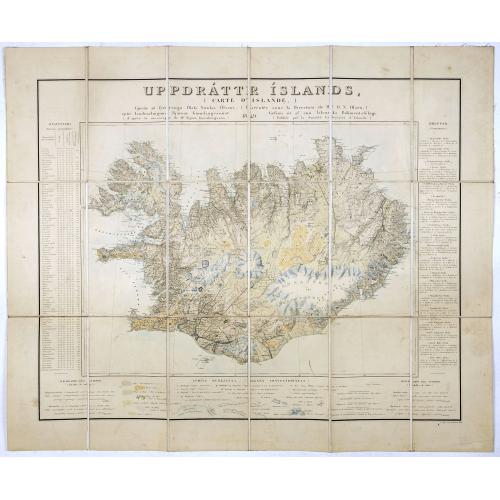

Uppdráttr Íslands / Carte d'Islande. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Description

To be clear, the present issue represents the second edition of the map, which is preceded by the first issue, dated 1844 (but actually published in 1848), that was printed on five large separate sections (4 sections for the map and 1 section for the legend), in a portfolio format, housed in covers. The present edition is notable in that it embraces the entire scope of the island in one integrated view, albeit at a reduced scale.

The amazing detail concerning Iceland’s physical and human geography, as showcased on the present map, is explained in the bilingual legend (Icelandic / French, as French was then a common pan-European academic language), which runs along the lower part of the composition, entitled ‘Signes Conventionnels’ (Conventional Signs). With respect to physical geography, the legend identifies ‘Montagnes et Collines’ (mountains and hills); ‘Lac’ (lakes); ‘Glacier’ (glaciers); ‘Ruisseau’ (creeks); ‘Rivière ou Fleuve’ (rivers); and uses sophisticated varieties of lithographic shading to denote ‘Sol marécageux’ (bogs); ‘Lave’ (lava beds); ‘Près et paturages’ (prairies or pasture lands); ‘Bois et broussailles’ (forest or brush lands); ‘Déserts arides et rocailleux’ (arid or rocky deserts); ‘Landes et Bruyères’ (tundra shrublands); ‘Sable’ (sandy lands); ‘Ravin et Crevasse volcanique’ (volcanic ravines and crevasses); ‘Source chaude ou bouillant et minerale’ (hot or mineral springs); and ‘Tournant’ (maelstroms, shown along coastal headlands).

As for Iceland’s human geography, the map uses symbols to identify ‘Ville’ (towns); ‘Eglise principale’ (main churches); ‘Eglise d’annexe’ (rural community churches); ‘Lieu de jurisdiction communale’ (town halls); ‘Etablissement de commerce’ (rural/general stores); ‘Pont’ (bridges); ‘Chemin’ (roads); ‘Ferme et habitation paysan’ (rural homesteads); ‘Ruines’ (ruins); ‘Stations trigonométriques’ (stations for taking trigonometric surveying measurements); ‘Pyramide itinéraire’ (pyramidal markers for orientation); as well as a series of lines demarcating the boundaries of various levels of political jurisdictions.

The detailed chart on the left-hand side of the map, ‘Positions geographiques,’ notes the geodetic coordinates of dozens of locations across Iceland, taken from Gunnlaugsson’s own astronomical readings. The chart on the right-hand side labeled ‘Communes,’ notes all of the towns and villages on the island, grouped by county.

During the period in which the present map was made, Iceland was a possession of Denmark, an arrangement that was becoming increasingly uncomfortable. Through the signing of the Old Covenant in 1262, Iceland lost its independence and became a vassal of Norway. From 1523, it was a part of the Norwegian-Danish Kingdom and, from 1814 onwards, Iceland was a vassal of Denmark. While Iceland had once prospered from trade with Norway, as Denmark came to dominate Iceland’s affairs, its economy suffered from the 17th Century onwards. Life was hard, as the island experienced several natural disasters (volcanic eruptions) and plagues, while Copenhagen was neglectful of its distant charge.

The coasts of Iceland had been completely surveyed to a high standard from 1776 to 1818, with the consequent charts printed in stages from 1788 to 1826. The Danish sea captain Hans Erik Minor commenced the scientific hydrographic charting of Iceland in 1776, who made fine charts of the southwestern coasts. His death in 1778 halted surveying activities, although many of his charts were printed in 1788, under the direction of Poul de Løvenørn, the founder of the Danish Hydrographic Office. Løvenørn sought for years to gain the funding to continue the coastal surveying of Iceland, which was finally granted in 1800. Surveying resumed in 1801 under the hydrographic department’s auspices. All of Iceland’s coastlines were charted to advanced trigonometric standards by 1818. All charts were published by 1826.

While sea captains and fishermen highly valued the new charts, they were of little consequence to most Iceland’s residents. Apart from topographical features located immediately on the littoral, there were absolutely no maps of Iceland’s interior or road systems. Civil administrators had no maps with which to plan policies and manage infrastructure, and local citizens had no access to maps labeling the locations of their homesteads. The lack of topographical maps was causing much frustration amongst Icelanders, and the Danish government’s seeming indifference to the matter was increasingly a cause of friction.

Enter Björn Gunnlaugsson (1788 - 1876), a brilliant and eccentric Icelandic mathematician who was responsible for creating the first modern map of Iceland. He hailed from a poor farming family in the remote northwest of the island. At a very early age, his uncommon intelligence impressed the clerics who ran the local country school. He was sent to Reykjavik, where he achieved extremely high grades in the baccalaureate exams. In 1808, the city’s bishop recommended that Gunnlaugsson be accepted to the University of Copenhagen. However, he could not travel to Denmark, owing to the ongoing Napoleonic Wars.

After many years, in 1817, Gunnlaugsson was finally able to enroll at the University of Copenhagen, where he studied mathematics and theology. He won the university’s prestigious Gold Medal for Mathematics twice, a feat that shocked the academic community, as they never expected such an accolade to be awarded (let alone twice!) to an obscure Icelander.

While Gunnlaugsson could have made a successful career in Copenhagen, he was wedded to Iceland and always vowed to return home. However, Iceland’s economy was perennially in the doldrums, and jobs outside of the fishing and farming sector that paid a living wage were few and far between. In 1822, he was relegated to accepting the position of Danish language, mathematics, and history teacher at the grammar school at Bessastadir, not far from Reykjavik. He was said to be an absolutely horrible teacher who delivered lectures on advanced calculus to students who could barely count up to ten on their hands. While he desperately needed the salary, he was bored stiff with his posting, and his mind was always on grander things.

Gunnlaugsson had a lifelong love for the austere beauty of Iceland’s landscape. By the late 1820s, his thoughts began to focus on the topographical mapping of the island. While something of an ‘odd duck’ and a loner, Gunnlaugsson was actually remarkably attuned to the needs and ambitions of the Icelandic people, and he seems to have been motivated by his countryman’s frustrations regarding the lack of comprehensive maps of their island.

In 1829, through contacts he made at university, Gunnlaugsson applied to the Danish crown for funding and equipment to conduct a comprehensive topographical survey of Iceland. Perhaps not surprisingly, he received no response. Relief came from the Icelandic Literary Society (Hið Íslenzka Bókmenntafélag). Founded in 1816, the organization promoted and strengthened Icelandic language, literature, and scientific learning. While the Icelandic Independence Movement did not yet exist (it would come into being in the 1840s), the Society was founded in response to Copenhagen’s neglect of the island. It would later become a nucleus for separatist sentiment.

The Society was highly impressed with Gunnlaugsson’s proposal and was convinced of the profound value of a topographical survey. However, it was also desperately short of funds and, initially, could only give Gunnlaugsson a modest grant lasting only one year. Gunnlaugsson asked the Danish government if he could borrow the advanced surveying equipment used to complete the triangulations of Løvenørn’s coastal surveys, but this request was ignored. The Icelander was thus compelled to rely upon desultory equipment, which made his task far more difficult.

During his allotted “trial year,” Gunnlaugsson proceeded to complete a survey of the Gullbringu and Kjósarsýsla counties, after which he dispatched his manuscripts to Copenhagen, whereupon a map was published, entitled Gullbríngu og Kjósar Sýsla med nockrum parti af Árnesssýslu (1831).

The Society was most pleased by this initial offering, and, with great difficulty, it managed to secure funds for Gunnlaugsson to conduct a systematic survey of the entire island. The original plan was for Gunnlaugsson to continue to survey each county. His manuscripts would be fashioned into individual county maps that would be serially published in Copenhagen, with a final general map of the island being assembled later. However, it soon became clear that this method would be too expensive. It was decided that Gunnlaughsson would proceed with his survey, making manuscript maps for each county, which would be assembled into a pan-island map only after the entire project.

Gunnlaugsson did not create his own baselines for triangulation but relied on those established by Løvenørn’s coastal surveys, which, fortunately, were quite accurate. From this foundation, he built out his own triangulations into the island’s exceedingly rugged interior.

From 1831 to 1843, Gunnlaugsson worked tirelessly, concentrating most of his energies on creating an accurate geodetic framework, with an emphasis on Iceland’s inhabited regions. From 1836 onwards, his efforts were assisted by adding a modest annual stipend from the Danish government. For a few uninhabited or challenging places, he was compelled to rely upon the geographical descriptions provided by local residents, placing this information into a correct context with relation to his own findings.

For the very first time, the outlines of Iceland’s vast glaciers, volcanoes, and lava fields were revealed on a map with a relatively high degree of accuracy. Likewise, the inhabited regions of the interior and the corridors along the inland roads appear with great planimetric accuracy and impressive detail. While Gunnlaugsson could not map some of the more remote areas, his coverage of the island was essentially complete. Especially given the rugged and forbidding nature of the terrain, and the fact that he was compelled to rely upon desultory equipment, his accomplishment was nothing short of astounding.

Enter Olaf Nikolas Olsen (1794 – 1848), a Danish military cartographer who, in 1842, was named as the Director of the Danish Topographical Office. Olsen was far more enlightened than his predecessors and did not share their dismissive attitude towards Iceland. He was a great admirer of Gunnlaugsson’s work and was instrumental in bringing the intended map of Iceland to publication. Olsen began to carefully compile Gunnlaugsson’s regional manuscripts maps into an accurate general map of the island.

By 1844, Olsen’s task was complete, and the map was prepared to be issued (in quarters) onto 4 large sheets, plus a text sheet, to a scale of 1:480,000, bearing the title Uppdráttr Íslands / Carte d’Islande…1844. For unclear reasons, while dated 1844, the five-sheet map was not actually published until 1848. However, once issued, the map was widely praised as a masterpiece of scientific cartography, being the first accurate and complete topographical map of Iceland. However, it was also criticized for being unwieldy. Icelanders and Danish government officials wanted a map that showcased the entire island in a single view.

Olsen died on December 19, 1848, however, he had largely finished the manuscript of the single-sheet edition, and his magnificent draftsmanship was preserved in the printed version. As the single-sheet version was intended to fulfill both a practical and decorative purpose, it was lithographed to an especially high technical standard by the master engraver F. C. Holm, with the careful addition of hand color, for details such as the coasts, glaciers, lava beds, as well as areas covered by vegetation. The single-sheet map was promptly published on a scale of 1:960,000 and became the definitive map of record of Iceland for the next half-century until the publication of Thorvaldur Thoroddsen’s surveys in 1900.

Björn Gunnlaugsson’s magnificent work was recognized by the Danish government, as he was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Danneborg in 1846. He was subsequently also conferred with the French Knight’s Cross of the Legion d’Honneur. The Gunnlaugsson-Olsen map was awarded a prize at the 1878 Paris Universal Exhibition as being one the best topographical maps of its era. Gunnlaugsson, for the remainder of his life, focussed on teaching, and ironically, despite his impossibly awkward classroom lectures, became Iceland’s leading educational reformer.

The Gunnlaugsson-Olsen map is scarce in either of its original two editions. We are aware of only one example of the 1849 integrated (single-sheet) edition of the map appearing on the market since 1969.

Reference: OCLC: 557726762; Haraldur Sigurðsson, Kortasafn Háskóla Íslands (Reykjavík 1982), pp. 7-15.

FAQ - Guarantee - Shipping

Buying in the BuyNow Gallery

This item is available for immediate purchase when a "Add to Cart" or "Inquire Now" button is shown.

Items are sold in the EU margin scheme

Payments are accepted in Euros or US Dollars.

Authenticity Guarantee

We provide professional descriptions, condition report (based on 45 years experience in the map business)

We provide professional descriptions, condition report (based on 45 years experience in the map business)

Paulus Swaen warrants the authenticity of our items and a certificate of authenticity is provided for each acquired lot.

Condition and Coloring

We indicate the condition of each item and use our unnique HiBCoR grading system in which four key items determine a map's value: Historical Importance, Beauty, Condition/Coloring and Rarity.

Color Key

We offer many maps in their original black and white condition. We do not systematically color-up maps to make them more sellable to the general public or buyer.

Copper engraved or wood block maps are always hand colored. Maps were initially colored for aesthetic reasons and to improve readability. Nowadays, it is becoming a challenge to find maps in their original colors and are therefor more valuable.

We use the following color keys in our catalog:

Original colors; mean that the colors have been applied around the time the map was issued.

Original o/l colors; means the map has only the borders colored at the time of publication.

Colored; If the colors are applied recently or at the end of the 20th century.

Read more about coloring of maps [+]

Shipping fee

A flat shipping fee of $ 30 is added to each shipment by DHL within Europe and North America. This covers : International Priority shipping, Packing and Insurance (up to the invoice amount).

Shipments to Asia are $ 40 and rest of the world $50

We charge only one shipping fee when you have been successful on multiple items or when you want to combine gallery and auction purchases.

Read more about invoicing and shipping

FAQ

Please have a look for more information about buying in the BuyNow gallery

Many answers are likely to find in the general help section.

Virtual Collection

![]()

With Virtual Collection you can collect all your favorite items in one place. It is free, and anyone can create his or her Virtual map collection.

Unless you are logged in, the item is only saved for this session. You have to be registed and logged-in if you want to save this item permanently to your Virtual Collection.

Read More[+]

Register here, it is free and you do not need a credit card.

Add this item to

Virtual Collection

or click the following link to see my Virtual Collection.

| High-Resolution Digital Image Download | |

|

Paulus Swaen maintains an archive of most of our high-resolution rare maps, prints, posters and medieval manuscript scans. We make them freely available for download and study. Read more about free image download |

In accordance with the EU Consumer Rights Directive and habitually reside in the European Union you have the right to cancel the contract for the purchase of a lot, without giving any reason.

The cancellation period will expire 14 calendar days from the day after the date on which you or a third party (other than the carrier and indicated by you) acquires, physical possession of the lot. To exercise the right to cancel you must inform Paulus Swaen Europe bv, which is offering to sell the lot either as an agent for the seller or as the owner of the lot, of your decision to cancel this contract by a clear statement (e.g. a letter sent by post, or e-mail (amsterdam@swaen.com).

To meet the cancellation deadline, it is sufficient for you to send your communication concerning your exercise of the right to cancel before the cancellation period has expired.