Hartman Schedel

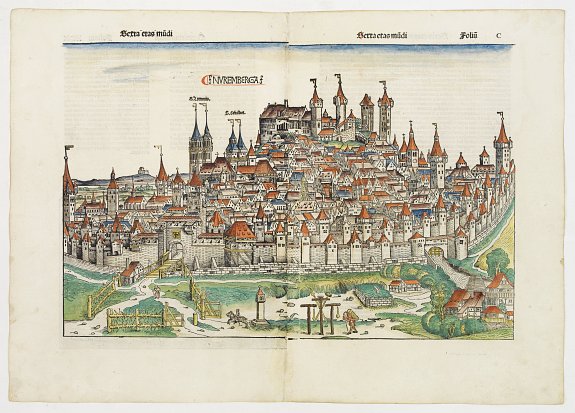

The LiberChronicarum or the Nuremberg Chronicle, as it is also known, is a history of the world from creation to 1493, dividing earthly history into six ages: from the creation to Noah, from Noah to Abraham, from Abraham to David, from David to the Babylonian captivity, from the Babylonian captivity to the birth of Christ and from the birth of Christ to the end of the world (or 1493 - blank pages were left for owners to fill in events after publication). Two further ages present future events. The Seventh Age is the age of the Antichrist and the Ultimate Age is the Last Judgment. It is one of the finest illustrated books of the fifteenth century with illustrations of biblical scenes, major cities, characters from myths and fables, the genealogical tables of emperors, kings and popes as well as maps.

The Liber Chronicarum was commissioned by two wealthy Nuremberg merchants and brothers-in-law, Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermaister.

They contracted Michael Wohlgemut (1434-1519) and his stepson Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (c.1460-1494) to make the woodcuts for the book and draw up layouts showing the setting of the type and the placement of the woodcuts. The text was supplied by Hartman Schedel (1440-1514), a physician and humanist scholar. Schedel supplied little original material for the work but relied heavily on the work of others including Jacob Philip Foresti of Bergamo, whose Supplementum Chronicarumn was reproduced almost word for word. For some of the contemporary material, he drew heavily upon

Historia Bohemica, Rome 1475, by Aneas Sylvius Piccolomini.

They contracted Michael Wohlgemut (1434-1519) and his stepson Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (c.1460-1494) to make the woodcuts for the book and draw up layouts showing the setting of the type and the placement of the woodcuts. The text was supplied by Hartman Schedel (1440-1514), a physician and humanist scholar. Schedel supplied little original material for the work but relied heavily on the work of others including Jacob Philip Foresti of Bergamo, whose Supplementum Chronicarumn was reproduced almost word for word. For some of the contemporary material, he drew heavily upon

Historia Bohemica, Rome 1475, by Aneas Sylvius Piccolomini.

While Liber Chronicarum contains much historical material it also gives much room to accounts of curiosities, myths and fables.

As notable as the material contained in Liber Chronicarum is what it leaves out. For example, the death of Lorenzo di Medici is not recorded nor is the adoption of Roman law in Germany. The

famous printer, Anton Koberger (1445-1513), the largest printer and publisher in Germany at the time, was employed to print the book.

At his height, Koberger ran 24 presses and employed 100 craftsmen.

The Latin edition was published on 12 July 1493, and a German edition, translated by George Alt, the city scribe of Nuremberg, was published on 23 December 1493.

Perhaps the most important features of the Liber Chronicarum are its design

and illustrations. The layouts for the illustration and typesetting of the book survive and show that the woodblock subjects were sketched at first and the text was then inscribed to fit within the

remaining space. The result is a marriage between text and illustration never seen before.

Perhaps the most important features of the Liber Chronicarum are its design

and illustrations. The layouts for the illustration and typesetting of the book survive and show that the woodblock subjects were sketched at first and the text was then inscribed to fit within the

remaining space. The result is a marriage between text and illustration never seen before.

The artists produced fourteen basic page layouts, with a number of variations, for the book. They cut

645 different blocks and used them several times for the final 1809 illustrations, the same cut often being used to illustrate different towns or people. For example, the woodcut that is used to

represent Damascus on fol. XVIII is used to represent Verona on fol. LVII and is also used to represent Mantua and Naples elsewhere in the work.

However, in some of the depictions of the more important cities such as Jerusalem and Constantinople, an effort has been made to put in recognizable landmarks. For example, we see the Temple of Solomon and other landmarks depicted in the woodcut of Biblical Jerusalem.

Some see evidence of the hand of Albrecht Dürer in some of the illustrations. Although this is possible, as he was apprenticed to Wohlgemut, this is doubted by other scholars.

In 1552, Schedel's grandson, Melchior Schedel, sold about 370 manuscripts and 600 printed works from

Hartmann Schedel's library to Johann Jakob Fugger. Fugger later sold his library to

Duke Albert V of Bavaria in 1571. This library, one of the largest formed by an individual in the 15th century, is now mostly preserved in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich.

Among the surviving portions of Schedel's library are the records for the publication of the work,

including Schedel's contract with Koberger for the publication of the work and the financing of

the work by Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister, as well as the contracts with Wohlgemut

and Pleydenwurff for the original artworks and engravings. The collection also includes the

original manuscript copies of the work in Latin and German.

The Nuremberg Chronicle receives much scholarly attention nowadays but the fact that some 800 examples of the Latin edition and 400 of the German edition are still in existence also testifies

to the popularity of the Liber Chronicarum in its own time also. In fact, it is estimated that around 1500 copies of the Latin edition and 1000 of the German edition were printed. It was popular

enough to be pirated.

The Nuremberg Chronicle receives much scholarly attention nowadays but the fact that some 800 examples of the Latin edition and 400 of the German edition are still in existence also testifies

to the popularity of the Liber Chronicarum in its own time also. In fact, it is estimated that around 1500 copies of the Latin edition and 1000 of the German edition were printed. It was popular

enough to be pirated.

Three years after the first edition was complete Johann Schönsperger (d. 1520) of Augsburg printed a version in German and went on to produce an edition in Latin and

another in German.

Further reading and books used in the compilation of this piece:

Adrian Wilson. The making of the Nuremberg chronicle. Amsterdam : Nico Israel, 1977.

Hartmann Schedel. Chronicle of the world : the complete and annotated Nuremberg chronicle of 1493, introduction and appendix by Stephan Füssel. Köln, London : Taschen, 2001.

Text by Hugh Cahill, Senior Information Assistant, Foyle Special Collections Library

Interesting reading and Translations of the text into English at the website of Morse Library.

was based on the cartographic system of Claudius Ptolemy, the great second-century AD geographer whose scholarship formed the foundation for map production in the fifteenth century.

Its configuration is ostensibly based on Ptolemy's second projection but simplified for a popular audience, without the scientific apparatus of latitudes, longitudes, scales and extensive nomenclature.

The map provides a window onto the late medieval imagination. The border contains twelve dour wind-heads, while the map is supported in three of its corners by the solemn figures of Ham, Shem and Japhet taken from the Old Testament.

Most remarkable are the panels representing creatures that were thought to inhabit the furthermost parts of the earth. There are seven such scenes to the left of the map and a further fourteen on its verso.

Among the scenes are a six-armed man, a centaur, a four-eyed man from a coastal tribe in Ethiopia, a dog-headed man from the Simien Mountains, a cyclops, a man with a single giant foot, a man with a huge lower lip, a man with ears hanging down to his waist, and other frightening and fanciful creatures.

Scholars estimate that approximately 1400-1500 Latin copies and 700-1000 German ones were printed. A document from 1509 has the final account of the sales of the two editions. It is interesting to note that 535 Latin and 60 German copies remained unsold. Approximately 400 Latin copies and 300 German ones survive today.