A rare and impressive pictorial Qing Empire map of the western part of Taiwan.

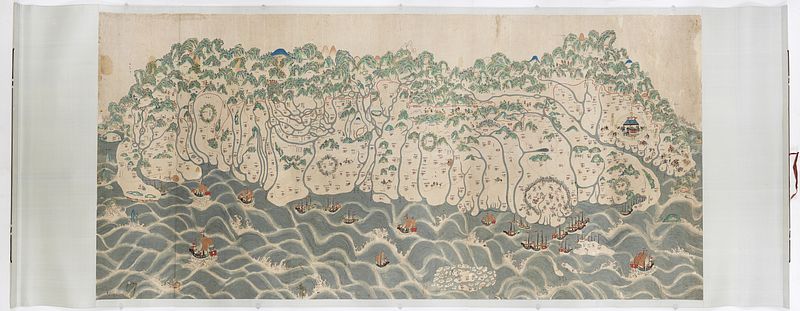

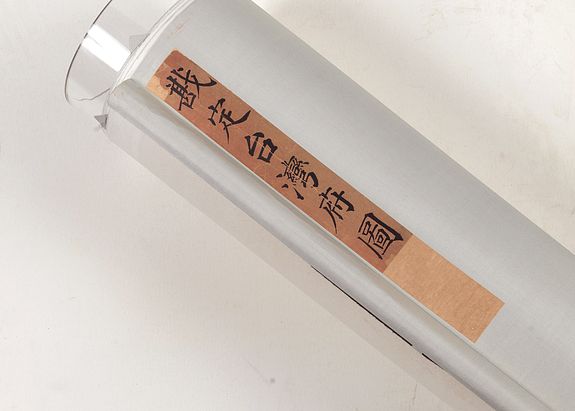

A rare and impressive pictorial Qing Empire map of the western part of Taiwan. Gouache on paper. Height 120 cm and Length 225 cm. (Taiwan, ca. 1850 and before 1879).

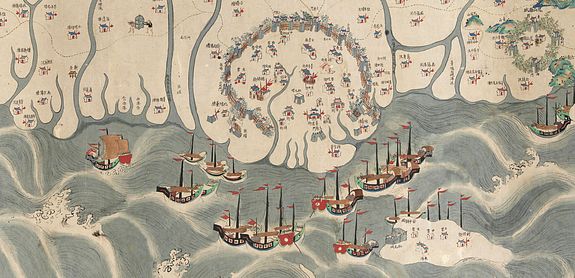

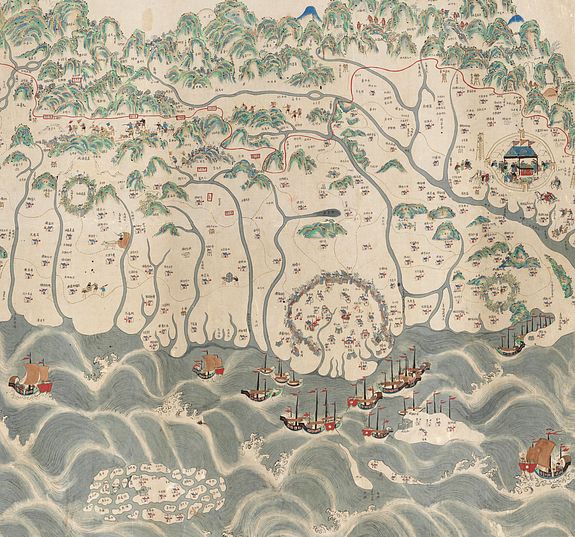

The map is filled with numerous small pictorial scenes of aboriginals at deer hunting and scenes of daily life. Chinese merchants, voyagers, military scenes, and arriving Chinese junks. Along the top is a red line., the so-called thóo-gû-kau (土牛溝, Dirt bull ditch).

The top of the map faces east, the bottom faces west, and the left and right are north-south. It is about 120 cm high and 225 cm long. The map shows only to the west of the Central Mountains in Taiwan, from Shamajitou in the south and Keelung Island in the north.

As the Qing Empire expanded, geographical knowledge about Taiwan, as one of its newly acquired lands, was crucial for strategic and administrative purposes. However, Qing maps of Taiwan made before 1879 depict only the western side of the island, while about three-quarters of the island is dismissed. This is because the Central Mountain Range that divides the island is notoriously difficult to cross, effectively cutting off the eastern half of Taiwan.

The first map to finally project a detailed image of eastern Taiwan was published in 1879 by Xia Xianlun 夏獻綸 in his Taiwan yutu bingshuo 臺灣輿圖並說 (Atlas of Taiwan with explanations).

Place names in various places with streets, villages, or houses are Han villages, while communities are Pingpu or aboriginal tribes. In addition, there are lines in the plain area indicating trade and postal roads. Although the whole map has no scale bar, the relative mileage between places is marked in the text.

After Qing acquired west coast Taiwan, the Qing government drew a line, the thóo-gû-kau (土牛溝, Dirt bull ditch), between the Qing territory and the Aboriginal territory. This line was drawn to prevent ethnic Han from grabbing and developing Aboriginal-owned lands and to try to keep the Aboriginals confined and minimize attacks.

Our map adopts the traditional Chinese "landscape painting" method. Although the map is different from the Western-style orientation, latitude,

longitude, scale, and accuracy, the map has rich humanistic connotations,

especially for the indigenous people. Much information about the nation is

unprecedented, and through this map, the original appearance of Taiwan's

time and space 175 years ago can be reproduced. It is an important

historical material such as history and geography, ethnic interaction,

immigration and reclamation, and the administrative system of the Qing

government.

The most distinctive feature of this map is the continuous

red line drawn from south to north. The red line is drawn from Fengshan,

Taiwan and Zhuluo counties in the south, and between Douliu Dongshan and Sulinzhuang in the central part

(approximately between Zhushan and Wufeng today).

The boundary is

defined in natural mountainous areas along mountains or valleys, with

rivers and banks, and in plain areas, where ditches are dug and piled up the soil to form Tuniu ditch. Boundary monuments prevent the aborigines

from leaving the plains, prohibit the Han people from entering the mountains and reclamation, and guard them with

watchtowers.

However, the divide didn’t function all that well. Han merchant groups continued to grab lands from the Aboriginals to gain access to valuable resources such as deerskin, farmland, and camphor. As they did this, the wronged Aboriginals would headhunt according to their tradition. So, Han merchant groups would hire militias to secure their interests, and these militias were referred to as Aiyungs.

A fine depiction of Tainan city on Taiwan’s southwest coast, which was the island’s capital from 1683–1887 under the Qing dynasty. Today, it’s known for its centuries-old fortresses and temples. One of its most famous sites is Chihkan Tower, an 18th-century Chinese complex with gardens, intricately carved towers and a temple erected on the foundations of Fort Provintia, a Dutch outpost dating to the mid-1600s.

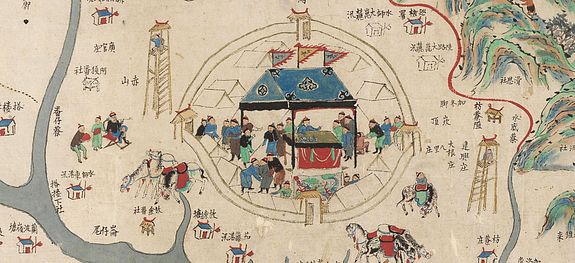

A depiction of present-day Pingtung City, which is still a county-administered city and the county seat of Pingtung County. The town is shown with important administrative servants inside the city walls. Many other early settlements with their defense walls are shown on the map.

Taipei fucheng

To the left on the map we see Taipei fucheng 臺北府城 (Taipei provincial capital) being the area of now-a-days Taipei.We also see the River

Taiwan and the Qing Dynasty

In the 23rd year of Emperor Kangxi (1684), Taiwan was officially incorporated into the territory of the Qing Dynasty. To present Taiwan's administrative and military defenses in detail, local officials hired special personnel to draw as many as 20 huge maps of Taiwan, which were presented to show the imperial court understand Taiwan's topography, landforms, and participation in governance reforms.

Therefore, at this time, the immigrants who crossed the sea from their original villages to Taiwan have gradually entered the mountainous areas of Ken Chiayi, resulting in the reduction of the living space of the aborigines, and the original rights and interests have been affected.

According to Shepherd, the Qing court alternated between a pro-quarantine approach and a pro-colonization approach to Taiwan policy throughout this period.

Pro-quarantine policies sought to preserve the status quo on the island by restricting Chinese immigration to Taiwan and protecting the indigenes’ land rights.

Pro-colonization policies promoted Chinese immigration and the aggressive appropriation of indigenous lands for Chinese settlers. Policymakers alternated between these two orientations, as they sought to balance the interests of the indigenous people and the Chinese settlers and thereby avoid costly conflict on the frontier.

Despite the efforts of pro-quarantine officials, the Qing could not stem the tide of Han Chinese immigration to this frontier, and by the nineteenth century, the court had decided to proceed with the final colonization of the island as a whole.

In 1875, the Qing adopted the “Open the Mountains and Pacify the Savages” (kaishan fufan) policy.

This policy legalized the entry of Han Chinese settlers into the last of the remaining indigenous territory on the island. In order to accomplish this appropriation of lands, the Qing employed the military to “pacify the savages.”

With the adoption of this policy, the tenuous balance between Han Chinese interests and indigenous interests was definitively tipped in favor of the Chinese settlers.

This policy legalized the entry of Han Chinese settlers into the remaining indigenous territory of Taiwan. Xia’s map embodies the results of that policy, by showing the Central Mountain range no longer as an obstacle between two halves of the island, and providing a new spatial image of Taiwan as a unified terrain.

When Taiwan was promoted to provincehood in 1887, it seemed that the island was to be once and for all Chinese terrain.

During the Qing conquest of Taiwan, a segregation policy was adopted to prevent disputes between the Minfans.

The Qing Dynasty ruled Taiwan and adopted the Han "fan" isolation policy. In order to protect the land rights of the aborigines, and for fear of the Han people colluding with the aborigines, they prohibited the Han people from entering the "fan land". The demarcation is the so-called "red line of soil cattle".

The "red line" refers to the boundary line drawn on the map. The official boundary could not stop the Han people from crossing the boundary and entering the reclamation. After a long time, the boundary site was annihilated, and the Qing court redefines the boundary many times. The lines were set over time and each new boundary of Minfan, goes further to the inner mountains.

Geography vs. cartography

The late 19th century was a period of imperialist expansion throughout Asia. The Qing court realized it had to start defining its boundaries in order to protect its territory."The Chinese understood the function of maps differently from Westerners, like the British. Chinese map-making practices did not emphasize mathematical projections. For the Chinese, a map was a broad illustration of a region based on written sources. "

A typical 19th-century Chinese map shows regional hierarchies and landmarks, such as the prefecture seats depicted as walled compounds, the trade routes marked bypasses, and the areas controlled by various chieftains. And unlike western maps, the Chinese maps themselves rarely contained distance measurements. Textual descriptions indicated distances between various landmarks. "The Chinese believed that maps could not adequately convey the geographical knowledge found in written sources."

The Penghu or Pescadores Islands, an archipelago of 90 islands and islets in the Taiwan Strait are shown. The largest city is Magong, located on the largest island, which is also named Magong. The sea is filled with Chinese junks.

As a new territory of China, Taiwan had plenty of fields, but a relatively small population, and the Chinese were attracted to Taiwan to cultivate the land. As more and more Chinese came, deers disappeared from the plains. Consequently, the deer hide export decreased and the livelihood of the aborigines was affected.

In the same time, there was a boom in rice export. During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were recurrent food shortages in

the southeastern provinces of China, and rice export helped to alleviate the problem.

From the late 17th to the mid-19th century, Taiwan traded only with the mainland.

During the time, China was a stagnant traditional economy. Its long-run GDP per head

was conjectured to be zero (Maddison, 1998). Had China been a growing economy, Taiwan

probably would have benefited more from the trade.

After the first Opium War of 1839–

1842, China was forced to open five ports for international trade. In 1860 Taiwan’s Tamshui

and Takao (Kaoshiung) were also open for trade. So after almost two hundred years of

closeness, Taiwan once again joined the international market.

Within only a few years, a

new industry was established in northern Taiwan.

Beginning in the mid-18th century, tea was the most important export from China

(Gardella, 1994). Most of the tea was produced in northern Fukien, but the booming tea

industry had no effect on Taiwan, even though before 1886, Taiwan was a prefecture of the

Fukien province.

After opening to trade, a Scotch merchant named John Dodd discovered

that northern Taiwan was suitable for tea growing and began to build a tea industry there.

In 1865, tea export from Tamshui was valued at 180,859 pounds. Twenty years later, the export

value reached 16,237,179 pounds, about 90 times of 1865.

At the end of the 19th century, tea became the primary export from Taiwan, surpassing sugar and rice. As for imports, opium was the most important, which sometimes accounted for more than 60% of the total import.

The waters between Taiwan and China must have been filled with Chinese and later foreign vessels to transport goods. Nowadays, the Taiwan International Evergreen Marine Ltd. is a worldwide leading container shipping company founded by Dr. Yung-Fa Chang in 1968.

Interesting reading

Teng, Emma. 2006. Taiwan's imagined geography: Chinese colonial travel writing and pictures, 1683-1895. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Xu, Yuliang. 2019. Guang xu shi si nian(1888). Taiwan: Yuanzu wenhua.