Speculative bubbles - The First financial crisis.

The three bubbles, French, British, and Dutch, started at different times but burst at about the same time: September 1720.

1. The South Sea Bubble, named after the British South Sea Company, lasted from January to September 1720.

2. The Mississippi Bubble, after the Mississippi Company in France, had begun a little earlier, in 1719.

3. The Dutch bubble started in March 1720 and derived from the other two bubbles.

The Bubble.

Speculation in shares was known as 'the Bubble', and the trade was known as "Wind-Handel" and "Wind-Negotie" (both meaning Wind-Trade), because the trader often didn't own the shares, and he also tried to talk up the price. Dutch companies formed in the Bubble tended to be local affairs associated with the cities where they were founded. Stock offerings were often public in name only, with local officials and other insiders buying up most or all of the stock.

It couldn't last, of course. There was no real regulation; instead, there was government connivance.

The South Sea Co. was founded in 1711, nominally to trade in slaves in the Americas (the "South Sea" was the southern Atlantic), but was a means for the British government to convert its debt to stocks that could be traded on the market. By 1720, debt conversion was the Company's primary business.

The Mississippi Company. John Law (1671-1729), the son of

an Edinburgh banker and successful financier, who established the "Banque Générale" in France in 1715, founded the Compagnie de l'Occident for the exploitation of the resources of French Louisiana after Antoine Crozat had surrendered his charter in 1717.

Law's reputation caused the stock to sell readily, and the organization soon enlarged the scope of its activities by absorbing other commercial companies, its name then being changed to the 'Company of the Indies'. Enormous profits were anticipated... and the increasing demand for its stock led to wild speculation.

In the summer of 1719, Law began comparing Louisiana to Ophir (the legendary site of King Solomon's mines). The stock went up from 500 livres per share to a peak of 18,000 in the summer of 1720, then collapsed in September, settling at about 500 in 1721.

In January of 1720, the directors of the South Sea Company similarly hyped a public offering. From 128 pounds per share, South Sea stock peaked at almost 1000 by the summer. Demand was high, but to attract even more buyers, the Company's directors sold stock on credit. Hundreds of British companies also sprang up, most of them dodgy or bogus, to take advantage of the boom.

Dutch investors came late to the party in the spring and summer of 1720. They mostly ignored Mississippi shares but eagerly went after South Sea shares when they hit the market. During the boom, some 40 Dutch companies raised capital. Most were legitimate and associated with one city or another. Very few Dutch companies were traded on the Exchange (Beurs), so trading in French, British, and Dutch "bubble" companies was carried on in coffee houses.

In the 1600s, Frederik Hendrik, the Stadhouder of the Netherlands, declared that trading in shares one didn't own ("blanco") was legally invalid, but all the cities except Amsterdam, Haarlem and Leiden ignored this. Even in Amsterdam, the trade flourished at Kalverstraat No. 29, the coffee house Quincampoix, named after the Paris street where John Law was headquartered (No. 65). The place figures in many of the book's satires and is recognizable in some of the engravings.

Tulip mania.

Tulip mania.

Tulip mania or tulipomania was a period in the Dutch Golden Age during which contract prices for bulbs of the recently introduced tulip reached extraordinarily high levels and then suddenly collapsed. At the peak of tulip mania, in February 1637, some single tulip bulbs sold for more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled craftsman. It is generally considered the first recorded speculative bubble (or economic bubble). The term "tulip mania" is now often used metaphorically to refer to any large economic bubble.

more tulipmania

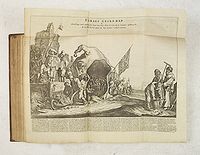

Floraes Gecks-Kap.

Floraes Gecks-Kap.

"Floraes Geks-kap Afbeeldinge van't wonderlijcke Jaar van 1637 doen d'eene Geck d'ander uytbroeyde, de luy Rijck sonder goet, en wijs sonder verstant waeren".

Satire on the tulip mania showing a fool's cap used as a tent. Inside the fools' cap, people are sitting around tables with scales, with an inscription above their heads 'De Comparitje', a flag hangs from the tent with two fools on it and an inscription underneath 'Inde 2 Sotte Bollen', on the right of the tent a woman named 'Flora' rides a donkey and an angry crowd is following her. In the foreground, people carry tulips and flower bulbs. Underneath the print text in Dutch and French.

The end.

The end came in the summer of 1720. John Law, running France's biggest company and its national bank, essentially was the economy.

In fact, Law introduced a paper currency to France, which could have worked out all right. However, when trouble hit,

Law began issuing financial decrees, forcing people to turn in their gold for paper money. He backed off, but then made other serious mistakes that killed off confidence in the company and the economy. When Mississippi's share prices plummeted, so did its capitalization and the national money supply. Law, abandoned by his protector, the Duc d'Orleans, fled to avoid jail, eventually washing up in Venice, living out his days as an unsuccessful gambler. The French government did OK since John Law had used the Company, via the Bank, to buy the government's debt when Company shares were at 10,000 livres.

The end came in the summer of 1720. John Law, running France's biggest company and its national bank, essentially was the economy.

In fact, Law introduced a paper currency to France, which could have worked out all right. However, when trouble hit,

Law began issuing financial decrees, forcing people to turn in their gold for paper money. He backed off, but then made other serious mistakes that killed off confidence in the company and the economy. When Mississippi's share prices plummeted, so did its capitalization and the national money supply. Law, abandoned by his protector, the Duc d'Orleans, fled to avoid jail, eventually washing up in Venice, living out his days as an unsuccessful gambler. The French government did OK since John Law had used the Company, via the Bank, to buy the government's debt when Company shares were at 10,000 livres.

The British collapse quickly followed the French one, but with less severe consequences. Britain had the Bank of England, an independent body that managed national finances, and Parliament acted quickly to introduce regulation. The courts tried the company directors, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the Postmaster General. The latter two were convicted of stock manipulation and insider trading and had their estates confiscated to pay damages. The British government, like the French one, had managed to offload its debt, so it came out all right.

Many Dutch investors were, of course, ruined also, and the crash took down legitimate companies as well as shady ones, but the Dutch economy wasn't affected. Dutch involvement was short, and the high price (€1,000 to €10,000 in today's money)

and limited availability of shares (in Dutch companies, anyway) also limited the fallout. The economy at the time was easily strong enough to weather the crash.

Damage in Britain was more widespread, mainly because there were more companies to buy into. France also suffered because the Mississippi Company was inextricably tied up with the paper economy. It recovered, more or less.

The South Sea and Mississippi Companies lasted until the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which triggered a serious financial crisis across Europe. The Rotterdam Lending Bank, later the City Bank of Lending (Stadsbank van Lening), existed until a few years ago, when it was acquired by Fortis Bank!

Naturally, the general bubble and its collapse in all three countries were fodder for much satire.

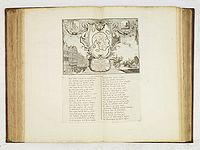

Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid.

Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid.

In Britain, there are a number of cartoons, including an early one by William Hogarth on the South Sea Bubble, and many satirical songs and broadsides. In France, a few.

But in the Netherlands, the Bubble gets a whole book. The general grotesquerie and the economic pointlessness of many of the Dutch "Bubble-companies" probably offended the Dutch Calvinist soul.

Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid : vertoonende de opkomst, voortgang en ondergang der actie, bubbel en windnegotie, in Vrankryk, Engeland, en de Nederlanden, gepleegt in den jaare MDCCXX is a matter of fact a collection of caricatural plates in prose and verse satirizing the first truly international speculative crisis in the history of financial

capitalism, the "Mississippi scheme" (1718-1720) of the French Compagnie d'Occident and the speculations its stock that led

to the complete ruin of many of its over-eager French, Dutch and English shareholders.

'The engravings, which illustrate the rise and fall of the great speculation, are full of humor; many of them are exceedingly ludicrous, and some very obscene… The number of plates in copies varies from 60 to 74" (Sabin). The book was anonymously published.

Not only are the plates worth studying as a historical document, it is also notable for examples of the textual and visual language we still use whenever a new "bubble" appears.

We offer for sale a very fine example of this book.

Bernard Picard.

A few plates in the book are signed by Bernard Picard. While Picart trained initially in Paris, establishing a studio on Rue St Jacques, au Buste de Monseigneur, in the late 1690s he found more work in the Netherlands.

Picart turned Huguenot and settled in Amsterdam around 1711.

Romeyn de Hooghe.

Many plates in the book are probably etched by Mr. Romeyn de Hooghe.

Romeyn de Hooghe was born in Amsterdam in 1645 and worked there until c.1680-1682, when he moved to Haarlem, where he died in 1708. For several Netherlandish provinces, he created interior architectural paintings and other works. In 1662 De Hooghe was invited by Adam Frans van der Meulen (1632-1690)

to Paris, where he etched the baptism of the Dauphin in 1668. There he met King Jan III Sobieski of Poland and was knighted by him in 1675.

De Hooghe painted, engraved, sculpted, designed medals, enameled, taught drawing school, and bought and sold art as a dealer. During the 1690s he made sculptures for the palace of Het Loo (1689-1692), designed and etched triumphal arches and medals for William III's entry into the Hague (1691), and designed the Haarlem market festival decorations for the peace celebration after the capture of Namur (1695). His political, legal, and economic interests are evident in his writings: Schouburgh der Nederlandsche Veranderingen (1674), Æsopus in Europa (1701), Spiegel van Staat des Vereenigde Nederlanden (1706), and Hieroglyphica of Merkbeelden

der oude Volkeren (1735), all of which he also illustrated. He was well-educated and may have attended law classes at a university in Harderwijk or Leiden.

De Hooghe's earliest print, after Nicolas Berchem, was made around 1662. He created about 3,500 images, most after his own designs, some after other artists, for himself and other authors, publishers, and printers. His plates were often retouched and adapted for later events, sometimes by De Hooghe, sometimes by others. He etched allegories and mythological scenes, portraits, caricatures,

political satires, historical subjects, landscapes, topographical views (especially of Netherlandish cities), battle scenes, genre scenes, title pages, and book illustrations. From 1667-1691 he illustrated various newspapers: Hollandsche Mercurius, Princelycke almanach, Orangien Wonderspiegel.

The first political iconographer of the Netherlands and its first great caricaturist, De Hooghe was closely associated with William of Orange. He repeatedly caricatured James II and Louis XIV, sometimes using pseudonyms on his most audacious images.

He was an expressive master of physiognomy, and his original, lively style displayed the baroque fashion for spectacular and allegorical fantasy. Romeyn de Hooghe was the most significant and prolific Netherlandish engraver in the second half of the seventeenth century.

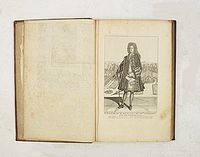

John Law.

John Law.

John Law was born in Scotland in 1671, the son of a Scottish banker. He received an education in political economy, commerce and economics in London. In 1694, however, he was forced to flee to Amsterdam after killing an opponent in a duel. There, he continued his education, studying banking.

In 1715, he settled in France and soon came to the attention of the Duc d'Orleans, regent for the young king of France. At the time, France was virtually bankrupt, partly a consequence of her lengthy and expensive foreign wars.

On May 20th, 1716, Law was granted a license to establish a 'Banque Générale' in France. The initial capital of six million livres was divided into 1,200 shares of 5,000 livres each. The shares were payable in four installments, one-fourth in cash, three-fourths in 'billets d'etat.' Law was authorized to issue notes payable on demand to the weight and value of the money mentioned at the day of issue, and on April 10th, 1717, it was decreed that Law's notes could be accepted in payment of taxes. The Banque Générale was very successful in regulating the paper currency, with the consequence that the interest rate fell to 4 1/2%, while the note issue rose to 60 million livres. In August of 1717, Law founded the 'Compagnie de la Louisiane ou d'Occident', which absorbed both the Louisiana Company founded by Antoine de Crozat in 1712 and the Compagnie du Canada. Law was granted extensive powers to exploit the Mississippi region - in French eyes, the area of North America watered by the Mississippi, and its tributaries. When one considers that these tributaries include the Missouri and the Ohio Rivers, the French laid claim to a vast area that also included regions claimed by the British.

The following year, Law purchased the tobacco monopoly in this region. Law's proposal to exploit the apparently limitless resources of the region - the Mississippi Scheme - caused a tremendous wave of interest, not just in France, but throughout Europe, and this encouraged the development across Europe of several other overseas companies, for example, the rapid expansion of the English 'South Sea Company' (founded in 1711), and a number of smaller companies in the Dutch Republic. In December 1718, Law's 'Banque Générale' was converted into the Banque Royale, with Law made a director. More importantly, the bank's notes were guaranteed by the king.

In 1719, the “Compagnie de la Louisiane” took over the “Compagnies des Indes Orientales et de la Chine”, with the new company being called the Compagnie des Indes. By this time, Law's reputation was truly in the ascendant. When he undertook to repay the national debt in return for control of national revenues and of the French mint for a period of nine years, the share price of the Compagnie rose dramatically in a frenzy of speculation.

Shares in the Company were originally issued at 500 livres, but rose to 10,000 livres during 1719. When the Company issued a 40% dividend in 1720, the share price rocketed to 18,000 livres, far outstripping the Company's capital base. At this point, speculators resolved to take their profits. The share price dropped as dramatically as it had risen. As panic set in, investors sought to redeem their bank and promissory notes, but the Company lacked sufficient coins and went bankrupt. Investors outside the Offices of the Mississippi Company in Quincampoix Street.

The effects were felt throughout Europe. Many European investors had invested in the French Company and were ruined. Moreover, confidence in other European companies was destroyed, and they, in turn, went bankrupt. Although undoubtedly a financial genius, Law was a victim of his inflated claims and his success. He fled from France, returned to his nomadic existence, and died penniless in Venice in 1729. The English South Sea Company was founded in 1711 and was granted a monopoly over trade to South America and the Pacific Islands.

The Company seems to have been run responsibly at first and achieved considerable success, indicated by King George III becoming governor in 1718. However, the directors were spurred on by the French example and, in 1719, they offered to take over the national debt of £51 million for a payment of £ 3.5 million and various other concessions. After competition from the Bank of England, the South Sea Company had to raise its offer to £ 7,567,00, an offer which was accepted in 1720.

The vast majority of the National Debt was held in the form of annuities. The Directors of the South Sea Company were relying on persuading holders of the annuities to exchange them for shares in the Company, but by inflating the share price so that a large proportion of the annuities could be canceled with the issue of a smaller value of shares.

Apparently, over half the annuity holders readily accepted the offer, again in the belief of the potential profits to be gained. However, unlike the Compagnie d'Occident, the South Sea Company actually had no geographical presence, so its future earnings were always going to be problematic. Once the Company had taken over the national debt, outside speculators and investors became more heavily involved in purchasing shares. In early 1720, the share price was 128 1/2d.

In June, the shares traded for 890d, and in July, they reached 1,000d. At this point, prominent investors indulged in profit-taking, not speculators as in France, but the directors of the Company themselves. With confidence eroded by the failure of the French scheme, the share price collapsed, falling to 135 by November. So serious was the matter that the House of Commons established a committee of inquiry into the company's affairs. It soon became apparent that the Company had been falsifying its accounts to inflate its profitability. More significantly, widespread corruption was uncovered.

The Company's negotiations with the government had been advanced by the distribution of bribes to individuals within the government The principal recipient was John Aislabie, Chancellor of the Exchequer. So serious were his offences that he was thrown out of Parliament and imprisoned. Others implicated were the equivalent of the Prime Minister, Charles Sutherland, Earl of Sutherland, the Secretary of State and the Postmaster General, although none was convicted. It is also possible that King George I was involved. As punishment, Parliament seized the assets of the Directors of the Company, raising over £2 million, of which about £1.68 million was used to assist investors bankrupted by the Company's failure.

Eiland Geks-kop.

Eiland Geks-kop.

AFBEELDINGHE van't zeer vermaerde Eiland GEKS-KOP. geligen in de Actie-ze, ontdekt door Mons.r Lau-rens, werende bewoond door een verzameling van alderhande Volkeren. die men dezen generalen Naam (Actionisten) geest.

One of the most famous cartographic curiosities, The island of Madhead showing

a man's head, wearing a fool's cap, with bell, but with the ears of a jackass.

Cartographic features are given punning names such as the River Bubble, the Island of Despair and the town of ‘Madmandam’. Principal names within the map:

QUINQUEPOIX: capital of the island, named after the headquarters of the Compagnie in the Rue Quimquempoix, Paris.

R: de Seine, R. de Teems & R. de Maas: the principal rivers of the three major countries involved: the Seine (Paris), the Thames (London) and Meuse (Amsterdam).

R: de Bubbel: Bubble River Z.Z. have: South Sea Haven, alluding to the English South Sea scheme.

M. have: ie Mississippi haven.

As such, it’s in the tradition of maps of Utopia, matrimony, or even gastronomy, which use the power of cartography to express abstract concepts.

The title translates Representation of the very famous island of Mad-head, lying in the sea of shares, discovered by Mr. Law-rens, and inhabited by a collection of all kinds of people, to whom are given the general name shareholders.

Readings & sources:

- Cole, Arthur H. The Great Mirror Of Folly (Der Groote Tafereel Der Dwaasheid), An Economic-Bibliographical Study). Baker Library,

Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration (Boston, 1949).

- Carswell, John. The South Sea Bubble, London, 1960.

- Gelderblom, Oscar and Jonker, Joost. Mirroring Different Follies: The Character of the 1720 Bubble in the Dutch Republic.

Paper 17 April 2008, published at Univ. of Utrecht. (a first draft).

- Kees Smit, Pieter Langendijk. Uitgeverij Verloren (2000, Hilversum), pp. 152-155.

- Stadsarchief Amsterdam image bank (Beeldbank) for images of the Quincampoix coffeehouse at No. 29 Kalverstraat (just south of the Dam)

- Wikipedia; South Sea Bubble, Mississippi Bubble, Windhandel.