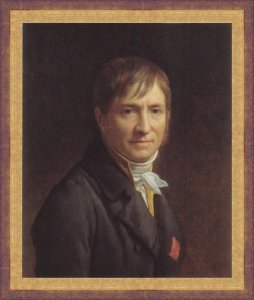

Pierre-Joseph Redouté

Pierre-Joseph Redouté (10th July 1759 in Saint-Hubert, Belgium - 19th June 1840 in Paris), was a Belgian painter and botanist known for his watercolors of roses, lilies and other flowers at Malmaison. He was nicknamed "The Raphael of flowers".

Pierre-Joseph Redouté (10th July 1759 in Saint-Hubert, Belgium - 19th June 1840 in Paris), was a Belgian painter and botanist known for his watercolors of roses, lilies and other flowers at Malmaison. He was nicknamed "The Raphael of flowers".

Pierre Joseph Redouté illustrated approximately 50 botanical books during his lifetime, making him one of the most prolific and widely celebrated botanical artists of the 18th and 19th centuries. Redouté became an heir to the tradition of the Flemish and Dutch flower painters Brueghel, Ruysch, van Huysum and de Heem. Redouté contributed over 2,100 published plates depicting over 1,800 different species, many never rendered before.

He was an official court artist of Queen Marie Antoinette and continued painting through the French Revolution and Reign of Terror. Redouté survived the turbulent political upheaval to gain international recognition for his precise renderings of plants, which remain as fresh in the early 21st century as when they were first painted.

Recognition in Paris.

Paris was the cultural and scientific center of Europe during an outstanding period in botanical illustration (1798-1837), one noted for the publication of several folio books with colored plates.

In 1782, through financial necessity, Pierre-Joseph, aged 23, joined his older brother, Antoine-Ferdinand Redouté (1756-1809), a painter of stage sets for the Théatre Italien in Paris. During the next few years, he worked in his brother's studio.

Although he could only paint watercolors in his spare time, the delicacy and realism of his art soon attracted much admiration including that of a Paris art dealer, Cheveau. Cheaveau arranged to have Redouté’s paintings engraved by Gilles-Antoine de Marteau who owned an engraving and color printing workshop. These first engravings caught the attention of the Dutch painter Gerard van Spaendonck (1746-1822), who immediately recognized Pierre-Joseph’s talent.

Van Spaendonck, professor of plant iconography (botanical painting) at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, appointed Redouté as a draughtsman at the Muséum. The Muséum was situated in the 28-hectare royal Paris botanic garden known as the Jardin du Roi. The Jardin des Plantes, as it was renamed after the French Revolution, is still France's main botanical garden today. It was here Redouté was introduced to a world of new and exotic plants and to the art of scientific botanical illustration.

London and printing technique of stipple engraving.

During a visit to London, arranged by L'Héritier in 1787, Redouté met Francesco Bartolozzi, who

introduced him to the concept of stipple engraving.

London and printing technique of stipple engraving.

During a visit to London, arranged by L'Héritier in 1787, Redouté met Francesco Bartolozzi, who

introduced him to the concept of stipple engraving.

This new technique used dots and lines rather than just lines to build the graduations of tone and compared to line engraving, produced a more delicate and realistic result. Bartolozzi also introduced Redouté to the process of single-plate color printing, a method that made it possible to add multiple colors to the plate and print it just once. Although sometimes, special copies had their final coloring touched up by hand.

Over time Redouté expanded these techniques further, inventing in 1786 his own trademark stipple engraving methods. His contribution to the art of print-making earned him the recognition of King Louis XVIII (1755-1824), who awarded him a medal for his achievements in 1796.

Later years.

In 1799, Joséphine acquired the château Malmaison in Rueil, western Paris. Her intention was to cultivate a magnificent garden at the château; a vast collection of plants including rare and seldom-seen specimens. No expense would be spared. Many were sourced from outside Europe and it was the Empress’s wish, to not only create a beautiful garden but to document every plant scientifically as well.

Under the auspices of the Empress, Redouté flourished.

His appointment was a well-remunerated one, enabling him and his wife, Marie-Marte Gobert, whom he had married in 1786, to maintain their apartment in Paris and in addition, buy a large country house and garden at Fleury-sous-Meudon. Although this property had suffered through neglect, they soon set about renovating the house and taming the wilderness back into a garden fit for the many plants Pierre-Joseph wished to grow.

After Joséphine’s death, Redouté’s income drastically fell, and he was forced to borrow money to maintain the lifestyle to which he, his wife and two daughters had grown accustomed.

Through the influence of his early mentor, Gerard von Spaendonck, Redouté again obtained employment at the Muséum. During this time he was joined by his younger brother, Henri-Joseph Redouté (1766-1852), who worked alongside Pierre-Joseph painting botanicals.

In 1822 Van Spaedonck died, and at the wish of King Louis XVIII, Pierre-Joseph succeeded him as

‘Maître du dessin au Muséum d'histoire naturelle’; professor of plant iconography at the Muséum.

For over 16 years he held this position, giving at least 30 public lectures per year on the practice and history of botanical painting. This brought him much notoriety and a steady stream of pupils from

France's high-ranking elite.