Printed in Japan

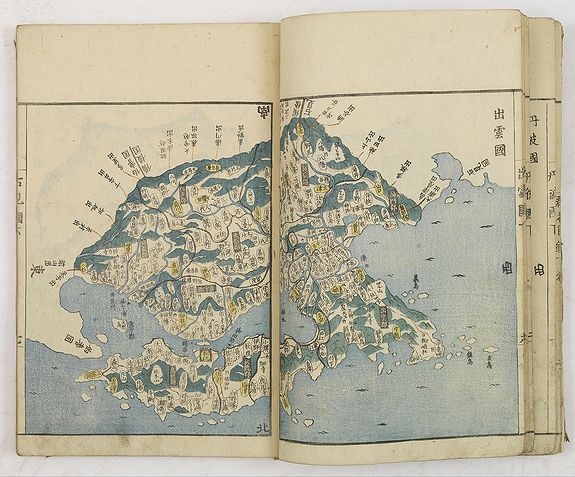

The Japanese cherish a great love for maps. Of old they adorned all kinds of objects with cartographic images of the world, of Japan, of their town or province. Before the Japanese came into direct contact with Europeans, they made maps that represented the Buddhist world. In that world there were only three great cultures, i.e. India, China, and Japan. For their overseas trade Japanese navigators relied upon their personal experience, traditional knowledge and rutters (travelogues).

The Japanese cherish a great love for maps. Of old they adorned all kinds of objects with cartographic images of the world, of Japan, of their town or province. Before the Japanese came into direct contact with Europeans, they made maps that represented the Buddhist world. In that world there were only three great cultures, i.e. India, China, and Japan. For their overseas trade Japanese navigators relied upon their personal experience, traditional knowledge and rutters (travelogues).

After the arrival of the Europeans, the Japanese realized that a much larger world existed outside of India, China, and Japan. The world maps created by the Flemish and Dutch cartographers like Abraham Ortelius, Gerard Mercator, Petrus Plancius, Willem Blaeu that the Dutch brought with them revealed what the unknown world looked like. However, European charts and maps were rare and expensive in Japan. Only rich merchants and officials of high rank could afford to buy them or could even set eyes on them. So, they ordered these modern western maps to be copied on screens. From the results it appears that not an accurate but an aesthetic representation of the map was most important - no exact copies, but the most beautiful screens resulted.

The free exchange with Europeans stimulated Japanese cartography. The printing technique improved. More accurate maps appeared in greater numbers. However, a broader circulation of western cartographic knowledge came about only after Japan closed their borders to foreigners, so that only in 1645 the first "modern" Japanese world map was printed, the Bankoku Sozu (general map of the world). This so-called Shoho map was a Japanese copy of a world map that an Italian missionary, Matteo Ricci, had made in China at the end of the 16th century. It was based on various Flemish and Dutch maps by Ortelius, Mercator, etc. Far into the 19th century it was frequently copied and reprinted so that gradually this 16th century world picture superseded the Buddhist three-culture map. An 18th century Japanese scholar even thought that in this period the Dutch packed their world maps in wooden boxes, filled up the seams with pitch and rope and then threw the boxes into the sea "as a gift to the world" in order to show how the various countries are situated on the globe. Such a map was supposed to have been washed ashore in Japan in the mid-17th century. Nevertheless, it wasn't until the end of the 18th century that the Japanese abandoned the 16th century world picture of the Shoho map.

An 18th century Japanese scholar even thought that in this period the Dutch packed their world maps in wooden boxes, filled up the seams with pitch and rope and then threw the boxes into the sea "as a gift to the world" in order to show how the various countries are situated on the globe. Such a map was supposed to have been washed ashore in Japan in the mid-17th century. Nevertheless, it wasn't until the end of the 18th century that the Japanese abandoned the 16th century world picture of the Shoho map.

The increasing interest for Dutch studies in Japan also led to the study of Dutch maps and atlases. In 1792, the famous artist-scholar Shiba Kokan made an exact copy of an 18th century world map of the Amsterdam publishing firm Covens & Mortier. Though this map had been obsolete for decades, for the Japanese the differences with the Shoho map bordered on the incredible. They acquired a lot of mostly 17th century Dutch maps so that in a short period in Japan all kinds of "modern" world maps were published, "recently translated from Dutch sources." Realizing that these "modern" maps were primarily 150 years old, Japanese scholars asked the Dutch to bring the most modern recent world maps to Japan. These were mostly maps by French and English cartographers who, during the 18th century, had surpassed the Dutch in cartographic knowledge. Based on these maps, the shogunate made a world map in 1810 that was completely up-to-date. In some instances the Japanese map was more accurate than any western world map.