Dutch impressions of the world in Japan.

By MIYOSHI Tadayoshi

Kobe City Museum

From the beginning of relations between Japan and the Netherlands, the VOC would bring maps to Japan to be presented to the Shogun and his court. We saw how in 1635, the Governor of Nagasaki gained information on a special map illustrating military affairs. A more general demand was always there for up-to-date maps of the world and globes.

One of the treasures of the Kobe City Museum is a screen decorated with a map of the world. On the reverse, there are four cities and figures in different costumes. This screen is based on the wall map of the world by Willem Jansz Blaeu, of 1607.

In the initial stages of Dutch-Japanese relations, VOC officials in Asia took good notice of the Japanese interest in maps. They had regular requests for these from the Netherlands. Some requests for Dutch wall maps are documented in the archives. In 1637, the governor-general in Batavia asked for six world maps. He wanted to use them as diplomatic gifts in the fortress town of Golconda (India) and Japan.

Seven years later, we find a similar and more specific request. In 1644, the governor-general requested new presents for Japan: among these were; a silver ship for the young shogun, several large globes and two large maps of the world. He said he wanted the kind of map usually seen in Dutch houses hanging on the wall like paintings. The maps should be decorated with figures in costumes of the different nations in the world. But, he added, please be careful that there are no crucifixes or saints depicted on the maps. The governor-general did not want to provoke the Japanese, who had just thrown out the Catholic Portuguese.

This last request is an interesting one. It gives us a contemporary impression of how people judge maps: this kind of world map was seen as not very different from a painting. We can be quite sure which world maps were actually sent following this request to be used in Japan: the wall map of the world that was published by Joan Blaeu in 1648. This beautifully hand colored map is preserved in the Tokyo National Museum.

There are still no copies in Japan of another wall map by Joan Blaeu that was published in 1646, an updated edition of his father's world map of 1619. The question arises: why didn't Dutch officials in Amsterdam respond to the request of 1644 and send this world map of 1646? The answer is simple. This map is not free from crucifixes and saints. For instance, it shows the mythical King of Abyssinia (Africa) seated on horseback, with a crucifix in his right hand. The anti-Catholic policy of the Tokugawa administration made it impossible to bring maps to Japan that had such illustrations. The governor-general in 1644 made sure that this message would not be misunderstood in Amsterdam.

North of Japan, Blaeu depicts a Japanese champan. This illustration is also there on the original map of 1619. The illustration is copied from one in the journal of the Dutch navigator Olivier van Noort. In December 1600, Van Noort met up with this Japanese ship in the Bay of Manila. The Japanese captain and Van Noort exchanged gifts: Van Noort gave him a banner with the colors of Prince Maurice and in return, he received an eight-year-old Japanese boy.

The Blaeu wall map of 1648 has been kept as a precious possession by the Tokugawa government. The shogun or someone close to him also had copies made of this map.

As we saw, Japanese charts betray no influences of Dutch ones. But the explorations by the VOC of the islands of Indonesia, the Gulf of Tonkin, Taiwan and the southwestern coast of Japan did reach Japan through Blaeu's world map of 1648. Joan Blaeu used the VOC charts of Visscher, De Vries and others to improve the depiction of the Far East.

This does not mean that world maps by Blaeu were in fact primarily valued as sources of information to be scrutinized for improved delineation of coastlines and islands. It seems that in the seventeenth century, and maybe, the first half of the eighteenth century, Japanese authorities valued the Dutch wall maps just as much for other reasons: for their beauty, their size, and their impression of the world. With this last aspect, I suggest that these wall maps could have been used as background in meetings with Dutch VOC officials. With the help of such a map, Dutch officials could explain, for instance, political events that had recently been taken place. The shogun and his court were keenly interested in these. They had no real need to keep up with minute changes on the face of the world map.

Screen with maps of the four continents

The Kobe City Museum possesses a screen that confirms just how highly Japanese officials valued Dutch maps. They valued them as much for their literary and artistic qualities as for their geographical information. It shows the four continents of Europe, America, Asia and Africa. Around each continent, there are smaller illustrations that show people in the costumes of the different regions of the continent concerned.

This screen was made by a very skillful and original Japanese artist. He simply copied Dutch examples - the maps and the borders with the costumes but the top seems to be a free compilation from different sources.

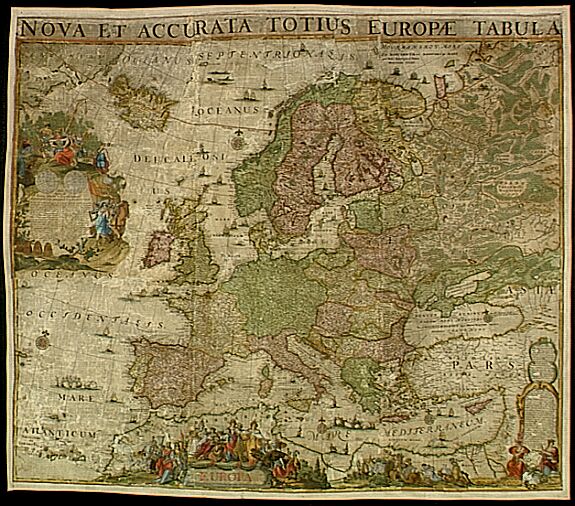

The maps are copied from Dutch wall maps of the continents. Frederick de Wit, and others, published these maps, copying each other. De Wit's map of Europe of circa 1670 and his maps of the other three continents was also copied by Gerard Valk. The set of Valk of circa 1695 is in its geographical content a copy of De Wit. However the decorations are changed. The Japanese artist copied the maps of Valk to make his maps of the continents.

Wall map of Europe by Valk.

Probably the maps of Valk were ones presented by Dutch officials of the VOC. The Dutch did not always present printed maps. On a few occasions, they also presented manuscript maps. In 1663 for instance, the Dutch presented 21 painted maps of which we know the prices but not their content. 11 large ones and 10 smaller ones. The large ones were valued at circa 30 pounds a piece : a sum for which you could buy a good painting in those days.

Concluding remarks

After 1630, the VOC rapidly improved its cartographical knowledge of the Far East in order to expand its trade in that area with the least risks to the ships involved. The improved Dutch charts of those years influenced the geographical information contained in Dutch printed maps of the period. Detailed maps and views of places in the Far East, like Taiwan and Osaka, made by Dutch artists, reached the Netherlands as well. These painted maps and views decorated interiors in order to display the history and the glory of Dutch expansion.

Dutch VOC chart makers used Japanese knowledge. Japanese chart makers on the other hand seem not to have been influenced by Dutch charts.

In the seventeenth century the shogun and members of his court certainly enjoyed Dutch maps, but less for the minute geographical details they contained, than for their artistic representation that offered an encyclopedic impression of the world outside. For that reason they ordered Japanese artists to imitate and 'translate' these maps onto screens.