Mapping of....

We hope you find your regions of interest in one of these short articles to help you bring them to life and supply interesting background information.

Select any region from the column on the left.

Arabia, Australia, Canada, China, Hungary, Invasion

of Minorca, Japan, Korea, Malta, Mer de l'Ouest, Northwest Passage,

Poland, Russia, South East Asia, Taiwan and Ukraine.

Or any of the following short articles series: about atlases, prints, town views and plans, mapmakers and explorers, map collecting and conservation, HiBCor Grading system, Prints, VOC and trading companies, Medieval Manuscripts, Speculative bubbles. See other subjects

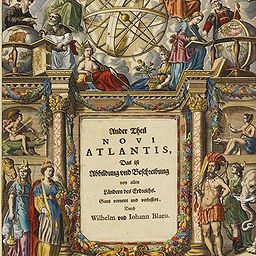

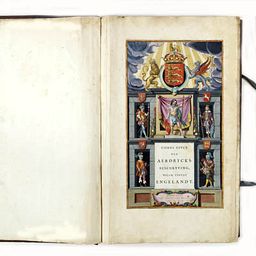

Read more about the backgrounds of some of the most important atlases published in the last 400 years.

Read more about the backgrounds of old maps. Maps come in different varieties like wall maps, road maps, sea charts, pictorial maps, etc.

-256x256.jpg)

Maps are in use throughout the world. Most of these maps can be placed into one of two groups: A) reference maps; and, B) thematic maps.

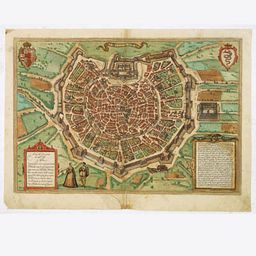

Read more about the backgrounds of some of the town plans and views published in the last 400 years.

Sometimes, maps become more famous than their makers. Still, others make a famous map, then disappear from history forever. A list of some famous mapmakers and explorers.

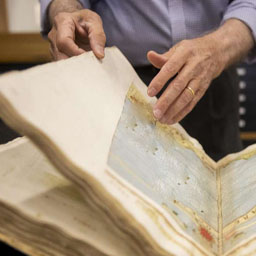

When you want to take good care of your maps and prints, you might find the following helpful information.

Read more about master colorist Dirk Jansz Van Santen, who used gold and sever and worked for Kings and wealthy merchants.