Henry S. Tanner and Cartographic Expression of American Expansionism in the 1820s

Article by : James v. Walker

AMERICAN'S CONCEPT of their nation’s sovereignty extending to the Pacific Ocean developed gradually and hesitatingly during the first three decades of the nineteenth century. Rhetoric about American interests in the Pacific Northwest included intermittent but intense international diplomatic conversations, presidential messages, congressional debates, editorial commentary in newspapers and other periodicals, and increasingly interested and opinionated cartographical literature. All these layers of discourse were linked by their focus on a geographical area and by geopolitical events centered on that area. That discourse contributed to a gradually developing image of an American dominion of continental proportions. Diplomats, congressmen, newspaper editors, and mapmakers were all involved in the development of that image but were not bound by similar conventions in the construction and communication of their visions. American commercial mapmakers of the period contributed to the development of a national consciousness of American expansion into the Pacific Northwest — a place still controlled by Native peoples — by both describing and interpreting national and international events.

During the second and third decades of the nineteenth century, the unique contributions of cartographers John Melish and Henry Schenck Tanner helped establish a national identity in ways that were visionary, influential, and powerful. Their maps contained information that was both geographical and geopolitical. In the Pacific Northwest, the main “new” features on updated editions of maps were often boundaries, legends, toponyms, and color codes that reflected the actions of non-Native diplomats and congressmen rather than explorers, topographers, and settlers. The maps graphically represented how American cartographers legitimized the expanding domain of one cultural group and, at the same time, delegitimized the sovereignty of both other imperial nations and Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest.

This detail of "A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America", published in 1814, was the most informative map of the Pacific Northwest at the time. Geopolitical events of the following decade resulted in John Melish and Henry Tanner drawing maps that promoted the expansion of American sovereignty in the region, despite the presence of large populations of Native Americans. Both cartography and geopolitical rhetoric helped construct an image of a distinct place in the Pacific Northwest called “Oregon.”

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the United States, Great Britain, Spain, and Russia all claimed sovereignty to some portion of the Native-controlled lands of the Pacific Northwest. By the middle of the second decade, Americans claimed rights principally on the basis of three historical events: Robert Gray’s discovery and naming of the Columbia River in May 1792; the military sponsored Expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark from 1804 to 1806; and the establishment of the private (but government sanctioned) fur trading enterprise at Astoria in 1811.(2) In the aftermath of the War of 1812, Anglo-American tensions increased regarding several issues, including contested areas of sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest. Still, American diplomatic activity regarding this region was restrained, and there was almost no physical presence of American military or commercial enterprise. Following the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814, formal restitution of Astoria from the British to the United States was delayed until August 1818. 3 The American government sanctioned maritime explorations to the Northwest coast in 1815 and 1816 but aborted them to more pressing needs for naval forces elsewhere.(4) Neither American nor British diplomats attempted treaty-making with any tribes of the region during this time.

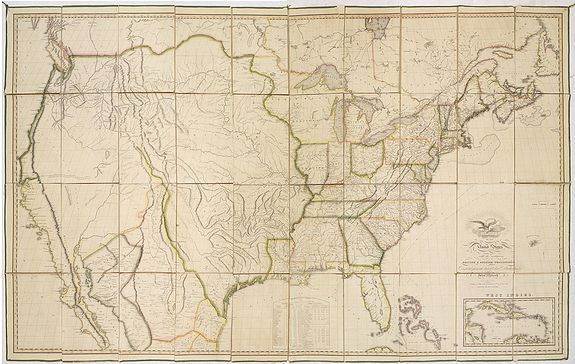

In contrast, publisher John Melish, an established and influential mapmaker in Philadelphia, advocated a more overt and opinionated position of American sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest. In 1816, he published his Map of the United States with the contiguous British and Spanish possessions ... (Figure 1). Scholars have widely regarded this map as the first to portray the United States extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific ocean.5 Indeed, in his accompanying Geographical Description, Melish stated: “The map . . . shows at a glance the whole extent of the United States territory from sea to sea.”6On the map, Melish extended the parallel of 49 degrees and 40 minutes across the Rocky Mountains to the Strait of Georgia as an extension of the “Northern Boundary of Louisiana” between American and British dominions. Melish redrew the forty-ninth parallel boundary several different ways as he frequently revised the map’s copperplates from 1816 to 1822. 7

Melish's 1816 interpretation of a forty-ninth parallel boundary extending all the way to the Pacific Ocean caught the attention of many, including Simon McGillivray, who was a principal partner of the British Northwest Company, which had established virtually the only non-Native presence in the Pacific Northwest at that time. In 1817, McGillivray published a pamphlet and map to demonstrate how the forty-ninth parallel boundary on Melish’s map would intersect British access to two important commercial transportation routes to the interior: the Columbia River and a (fictitious) Caledonia River, which his map showed flowing into the Gulf of Georgia below 49 degrees.8 McGillivray’s influence on British diplomatic policy exemplifies the strong, direct connection between British commercial interests and diplomatic activity during boundary negotiations with the United States from 1817; to 1846.

Figure 1: Map scholars have considered John Melish’s 1816 "Map of the United States with the Contiguous British and Spanish Possessions" the earliest map to illustrate the United States extending from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific.

During the first Anglo-American negotiations in London in 1818, United States plenipotentiary Albert Gallatin acknowledged the apparent veracity of McGillivary’s map.(9) He presented an unofficial modification of the American position (which advocated establishing the forty-ninth parallel from the Rocky Mountains to the sea) by offering to cede territory along Puget Sound and Admiralty Inlet to accommodate British access to the mouth of the Caledonia River (a position to which Gallatin returned during the negotiations of 1826). The negotiations of 1818 ended, however, with an agreement to formally extend the boundary along the forty-ninth parallel from the Lake of the Woods only to the Rocky Mountains. 10 As map scholar and historian Daniel Clayton asserts: “In the negotiations of 1818 cartography and diplomacy, image and assumed reality were tightly bound.”11

During these negotiations, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams was also consulting with Spanish minister Luis de Onís, culminating in the Adams-Onís Treaty of February 1819, which established the forty-second parallel from north of the headwaters of the Arkansas River to the Pacific

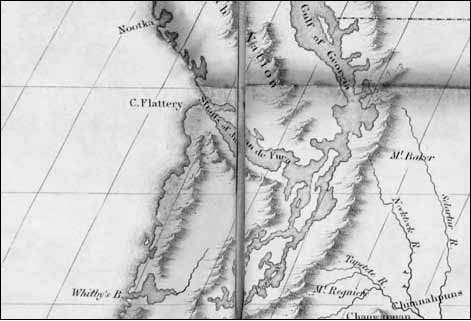

Figure 2: On one of the revised copperplates of 1820, Melish redrew the forty-ninth parallel boundary in a straight line extending to the sea by transecting the lower part of Vancouver Island (see detail at left).

Ocean as a boundary between United States and Spanish territorial possessions. This treaty effectively removed Spain from geopolitical hegemony in the Pacific Northwest and formally legitimized (from the non-Native perspective) an American reach to the Pacific Ocean. Adams and Onís used an 1818 edition of Melish’s Map of the United States during these negotiations, and an April 1819 revised edition of that map was the first to depict the new boundary along the forty-second parallel.12 In 1820, Melish again revised the forty-ninth parallel boundary by extending it in a straight line from the Rocky Mountains across the lower part of Vancouver Island to the ocean (Figure 2). This image of an area of American dominion bounded by the forty-second and forty-ninth parallels and by the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains reflected the boundary proposed by the United States in the negotiations of 1818 in London. It was also a position of advocacy by Melish, for the boundary had not been agreed on by American and British diplomats at the end of those negotiations.

Thus, at the close of the second decade of the nineteenth century, the United States, Great Britain, and Russia all claimed sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest with no mutually agreed-upon northern boundary above 42 degrees. Those nations did not recognize Native sovereignty in the region. The United States had no military presence in the area, and the only American commercial activity centered on a few vessels trading along the coast.13 West of the Continental Divide, only the British were engaged in fur trapping activity.14 There was furthermore little or no public discourse about American expansion to the Pacific Northwest, except for a few vocal exponents such as Thomas Hart Benton, who, as editor of the St. Louis Enquirer, had advocated in a series of editorials in 1818 and 1819 for the establishment of an American presence on the Columbia River.15 Many United States statesmen, including President James Monroe, Secretary of State John Adams, and Albert Gallatin, shared Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an expanded American identity into the Pacific Northwest, whether as part of the Federal Republic or as an independent Republic. Nevertheless, as the distinguished American historian Frederick Merk said, “The conviction that a new republic would come to life in the Pacific West was, however, not a policy,” or at least not a policy government officials strongly articulated to the public.16 In his Annual Messages to Congress from 1819 to 1821, Monroe did not discuss the recent Adams-Onís Treaty with Spain in terms of its geopolitical advantages in the Pacific Northwest. Instead, he expressed concerns about delays to ratification of the treaty in Madrid, the geographical importance of the cession of (East and West) Florida, and of the need to maintain neutrality with respect to civil wars in “Spanish Provinces in this hemisphere.” In his references to the 1818 negotiations with Great Britain, Monroe also had little to say about boundaries, instead focusing on the other articles of the convention dealing with commerce, fishing rights, and restitution for “the carrying away, by British officers, of slaves from the United States” in violation of the Treaty of Ghent.1 During this same period of 1819 to 1821, coverage by the National Intelligencer newspaper reflected these international concerns as well as pressing domestic issues such as the Missouri Compromise and Congress’ ongoing efforts to appropriate Indian territory by treaty, military force, and removal.18

Textual and cartographic literature of the time also reflected little that was either distinctive or consistent in naming areas of the Pacific Northwest. In publications prior to 1822, labels and references to the Pacific Northwest were vague and general: “the northwest coast of the continent” or “the coast contiguous” or “northwest coast of America westward of the Stony Mts.” or “the whole country on the waters of the Columbia River,” and so on. When specific names were used, such toponyms as “New Caledonia” or “Columbia District” or “Western Territories” appeared inconsistently on maps of the Pacific Northwest. Indeed, for most United States citizens, including most members of Congress, geographical knowledge of the Pacific Northwest was rudimentary or simply erroneous.19

In December 1820, House of Representatives member John Floyd of Virginia was appointed head of a committee “to inquire into the situation of the settlements upon the Pacific ocean [sic.], and the expediency of occupying the Columbia River.”20 The report of this committee on January 25, 1821, was accompanied by a bill “authoriz[ing] the occupation of the Columbia River.”21 This legislation was cited by an early twentieth-century historian as a “pioneer report . . . in its expression and embodiment of the ideas and impulses that were to shape the progress of events,” although it was anything but progressive in how it applied to Native Americans in the area.22 Floyd’s lengthy report on the history of exploration, commerce, and right of settlement in the region of the Columbia River included no possibility of recognition of independent Indian sovereignty, and the first section called for “extinguish[ing] the Indian title to a district of country not exceeding — — miles square.”23

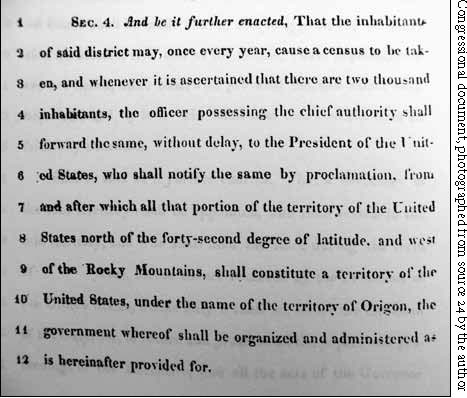

Floyd subsequently modified his proposal to include stronger advocacy for extending American jurisdictional sovereignty over territory within the Columbia River drainage area. He did this by introducing a new name for the territory. On January 18, 1822, Floyd issued a new report that included a revised bill in fourteen sections. Section four stipulated that the area settled should be called the “territory of Origon” [sic.] (Figure 3).24 This bill was the first use in text of the toponym “Oregon” applied to a geographical region of the Pacific Northwest instead of to a river. On January 19, the National Intelligencer published Floyd’s bill, accompanied by an editorial, and thereby introduced the public to the new toponym.25 Within four months, Henry Schenck Tanner (186–1858), a prominent Philadelphia-based map publisher, copyrighted his A Map of North America. He borrowed Floyd’s term (with changed spelling), and for the first time on a printed map, the toponym “Oregon Terry.” was applied to a broad region extending east from the Pacific Northwest.

Thus, through both published Congressional debates and cartographic literature, two concepts emerged into public consciousness. The first was the idea of Oregon as a place in the Pacific Northwest, and the second was the idea that this place should become solely an American possession. Within the span of a few months in 1822, a politician and mapmaker introduced the name Oregon in a thoroughly American context, applying it to an area of the continent whose ultimate sovereignty among non-Natives was not to be determined until the Oregon

Figure 3: Section four of Floyd’s bill called

for the creation of “territory of Origon” when the population of the area bounded by the forty-second parallel and the Rocky Mountains reached two thousand inhabitants. The bill did not suggest what should constitute a northern boundary of the territory.

Figure 3: Section four of Floyd’s bill called

for the creation of “territory of Origon” when the population of the area bounded by the forty-second parallel and the Rocky Mountains reached two thousand inhabitants. The bill did not suggest what should constitute a northern boundary of the territory.

Treaty of 1846 between the United States and Great Britain. 26 In subsequent debate, Floyd defended his choice of the name Oregon for a proposed territory in the Pacific Northwest, and at one point, he rejected an amendment changing the name to Columbia. It appears that neither Floyd nor Tanner ever conjectured on the possible origins of the name they adopted in 1822.

Recent scholarship, however, has demonstrated the rich and complex linguistic and cultural Native American heritage of the word Oregon. This research has provided further contextualization of a discussion on how the name Oregon on maps came to be identified with one cultural entity, but was originally drawn from another. In 2001, Scott Byram and David Lewis postulated that Oregon was derived from a Chinook Jargon trade word ooligan, the name of a fish from which was rendered a highly valued commodity oil or grease.27 The authors suggested that during extensive trade networking, Chinook speakers of the Pacific Northwest may have introduced the word ooligan, which would have been pronounced “urigan” or“oorigan” by Algonquian speaking Western Cree people east of the Rocky Mountains. The word may then have been introduced to Europeans in the vicinity of the Great Lakes region.

More recently, linguist Ives Goddard and anthropologist Thomas Love theorized that the term wauregan was used by Mohegan Indians of eastern Connecticut to describe the Ohio River as “good or fine or showy.”28 An English transliteration to Ouragon or Ourigan may then have been applied to a conceptualized western-running river, labeled “Belle Riv” or Beautiful River, depicted on a map by Antoine-Simon Le Page Du Pratz and published in 158. In both scenarios, the word Ouragon or Ourigan was first used by British officer Robert Rogers in a 165 written petition to the King of England to underwrite an expedition to find a Northwest Passage, in part by seeking “the river called by the Indians Ouragon.” Rogers subsequently sent one of his former officers, Jonathan Carver, on an expedition into the interior west of Lake Superior in 166 and 167. Carver’s popular account, Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America . . . , was published in London in 178, and over thirty editions of Travels and New Universal Travels were published in several languages.29 The word Oregon first appeared in print in text and on one of the two maps (spelled Origan) in this book, in both cases applied to a conceptualized River of the West.30 The text and maps of Carver’s Travels influenced the cartography of western North America for the next twenty-five years, as the word Oregon became synonymous with the “Great River of the West” and, later, the Columbia River.

This was the complex background of the place-name Oregon that was inherited but not recognized by John Floyd and Henry Tanner or by their American and European readership. Nor did any cartographers or readers appreciate the significant irony embedded in that heritage. Oregon was a place-name with undisputed Native American origins, used by British officers to identify a river on a French map, and then adopted by Americans in an openly anti-British context.

The year 1822 ended with an abrupt shift in the map-publishing community’s center of influence. John Melish died in December, and map publisher Andrew Goodrich of New York purchased his copperplates and inventory. Melish’s productivity had been remarkable, and according to map scholar Walter Ristow, “five U.S. presidents are known to have possessed copies of [his] large map of the country.”31 Tanner had been associated with Melish for several years, but by 1822, Tanner was independently successful as an engraver, cartographer, and publisher. With Melish’s death, Tanner’s firm became the preeminent center of United States commercial cartography.

Tanner’s A Map of North America Constructed According to the Latest Information was a large (43-by-58 inches) hand-colored copperplate engraving that was submitted for copyright on May 27, 1822 (Figure 4). It was available to subscribers in late 1822 as the fourth folio of his New American Atlas and was published in full with the fifth and final folio in 1823. 32 The final compilation included a title page, index of all the maps, and a Geographical Memoir of eighteen pages dated by Tanner on September 10, 1823. The title of the complete work is noteworthy because of the sources and authorities Tanner claimed for his map: A New American Atlas Containing Maps of the Several States of the North American Union, Projected and drawn on a Uniform Scale from Documents found in the public Offices of the United States and State Governments, and other Original and Authentic Information. ... No information is available on the number of copies printed.